Cloning the past to save the future?: The Mammoth Mission

A lifelike reconstruction of a woolly mammoth is shown in close-up, its long tusks sweeping forward as warm light reveals the texture of its skin and fur. The dark background isolates the animal’s features, emphasizing its iconic Ice Age anatomy.

The idea of bringing back the woolly mammoth, a creature that thundered across the Ice Age steppe and vanished only four millennia ago, sounds like myth, science fiction, or ecological wish-making. Yet today, it stands at the frontier of biotechnology, climate strategy, and conservation ethics.

Natural history and ecology

Woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) were colossuses of the Pleistocene steppe-tundra, reaching nearly four meters in height and over five tons in weight (Britannica, 2025). Their anatomy—double-layered fur, fat humps, reduced ears, and dense skin—was shaped by millennia of ice-age adaptation. Emerging roughly 600,000–800,000 years ago, woolly mammoths spread across Eurasia and North America via Beringia, coexisting with early humans who hunted them and left enduring cultural traces (Revive & Restore, n.d.).

The species dominated Ice Age biomass, and their foraging behavior—grazing vast grasslands, trampling snow, and dispersing nutrients—functioned as ecosystem engineering. Their extinction left ecological voids: shrubs replaced open grasslands, fire regimes shifted, permafrost thaw accelerated, and carbon locked in frozen soils began to destabilize (National Park Service - U.S. Department of the Interior, 2015).

When humans walked with Mammoths

Humans and mammoths were entwined for tens of thousands of years. Ivory carvings, Chauvet’s 32,000-year-old cave paintings, and over a hundred depictions in Rouffignac underscore their symbolic and practical significance. Their bones became tools, shelters, and art. Modern science began to understand them slowly: Hans Sloane (1728) identified mammoth bones as elephant remains, while Georges Cuvier (1796) established extinction as a real phenomenon. Later, the Lewis & Clark expedition (1803) confirmed their absence in North America, cementing their fate.

A Paleolithic charcoal drawing from the Rouffignac Cave—known as the “Cave of the Hundred Mammoths”—depicts a woolly mammoth surrounded by other Ice Age animals. The delicate lines etched onto the limestone wall highlight how early humans observed and revered the megafauna they lived alongside. © Bradshaw Foundation.

Genetic insights from Permafrost

Frozen remains preserved in Siberian permafrost revolutionized our understanding. Ancient DNA (aDNA) studies, environmental DNA (eDNA) from sediments, and full-genome sequencing have revealed complex population dynamics, local adaptations, and cold-adaptation genes critical to survival (Murchie, n.d.; Gross, 2006; Stephens, 2021; Science, 2005). eDNA indicates mammoths persisted regionally until 9,000–5,700 years ago, much longer than fossil evidence alone suggested, highlighting gradual, region-specific decline.

The Wrangel Island population exemplifies genetic challenges: despite expanding from just eight founders to several hundred individuals, inbreeding and mutation load contributed to eventual extinction, emphasizing the critical role of genetic diversity (Kuta, 2024). Studies of the Krestovka and Adycha lineages show that cold-adaptation traits—fur growth, fat deposition, thermoregulation—evolved over more than a million years (Stephens, 2021).

How ancient DNA is extracted

According to the Science Learning Hub (2023), museums hold vast collections suitable for ancient DNA study, including bones, mummified tissues, plant remains, and medical archives. Extraction protocols often involve careful sampling, pulverization, decalcification, enzymatic digestion, phenol–chloroform extraction, centrifugation, and PCR amplification. Scientists face major challenges: low DNA quantity, fragmentation, chemical damage, and contamination.

Ancient DNA enables studies of evolution, speciation, extinction causes, climate impacts, and species identification. Recent non-destructive techniques now allow sequencing without damaging valuable fossils, expanding our capacity to understand extinct ecosystems and the biology of lost megafauna.

Distinguishing Ice Age giants

Barney (2025) contrasts three Pleistocene megafauna:

Woolly mammoth (M. primigenius)

Cold-adapted, 2.7–3.3 m tall, ~6 tons, social, grazers of steppe-tundra.Columbian mammoth (M. columbi)

Larger (up to 4.5 m, 11 tons), less hairy, adapted to warmer North American environments.American mastodon (Mammut americanum)

Not a mammoth; forest-dwelling browser with conical-cusped teeth, straighter tusks, and more solitary habits.

Their extinctions left cascading effects on ecosystems, altering vegetation, fire cycles, and nutrient flows.

From ancient DNA to de-extinction: cloning, genetic engineering, and ecological proxies

Advances in ancient DNA (aDNA) research have paved the way for modern biotechnological ambitions to bring back aspects of extinct species. Sequencing the 13-million-base-pair nuclear genome of a 27,000-year-old Siberian mammoth (Science, 2005), along with even older DNA of 1.2 million years (Stephens, 2021), revealed key cold-adaptation mechanisms and confirmed the close evolutionary relationship between mammoths and Asian elephants.

These genetic insights now inform de-extinction strategies that combine two complementary biotechnologies: genetic engineering and cloning. As Ianello, Sevciuc, Ortiz & Visintin (2013) explain, genetic engineering involves modifying DNA directly—isolating genes, constructing recombinant molecules, transforming host cells, and verifying expression. Cloning, particularly reproductive cloning, produces a genetic copy through nuclear transfer without altering gene sequences.

Modern efforts blend both approaches: CRISPR-based engineering introduces mammoth genes into Asian elephant genomes, while cloning-like techniques help gestate viable embryos. The aim is not to create an exact replica of the woolly mammoth, but rather a functional ecological proxy—an animal capable of performing key ecological roles once fulfilled by its Ice Age ancestor, such as compacting snow, maintaining grasslands, and stabilizing permafrost.

These cutting-edge techniques build upon centuries of genetic discovery: from Mendel’s laws and Johannsen’s coining of the term “gene,” to Watson & Crick’s double helix, and the advent of recombinant DNA technologies using ligases and restriction enzymes. In this way, the resurrection of mammoth traits represents both a scientific milestone and a potential tool for ecosystem restoration.

The Vision of Colossal Biosciences

Colossal Laboratories & Biosciences (n.d.) frames de-extinction within five core objectives:

Reinforce climate-vulnerable Arctic ecosystems.

Improve survival tools for modern elephants.

Explore cold-adaptation biology.

Advance large-scale genetic engineering methods.

Demonstrate the feasibility of reviving lost megafauna.

Using Asian elephants—sharing 99.6% of mammoth DNA—researchers isolate preserved mammoth genes and insert cold-adaptation traits, aiming for animals that can compact snow, maintain grasslands, and stabilize permafrost, mitigating carbon release (Mann, 2018; Revive & Restore, n.d.).

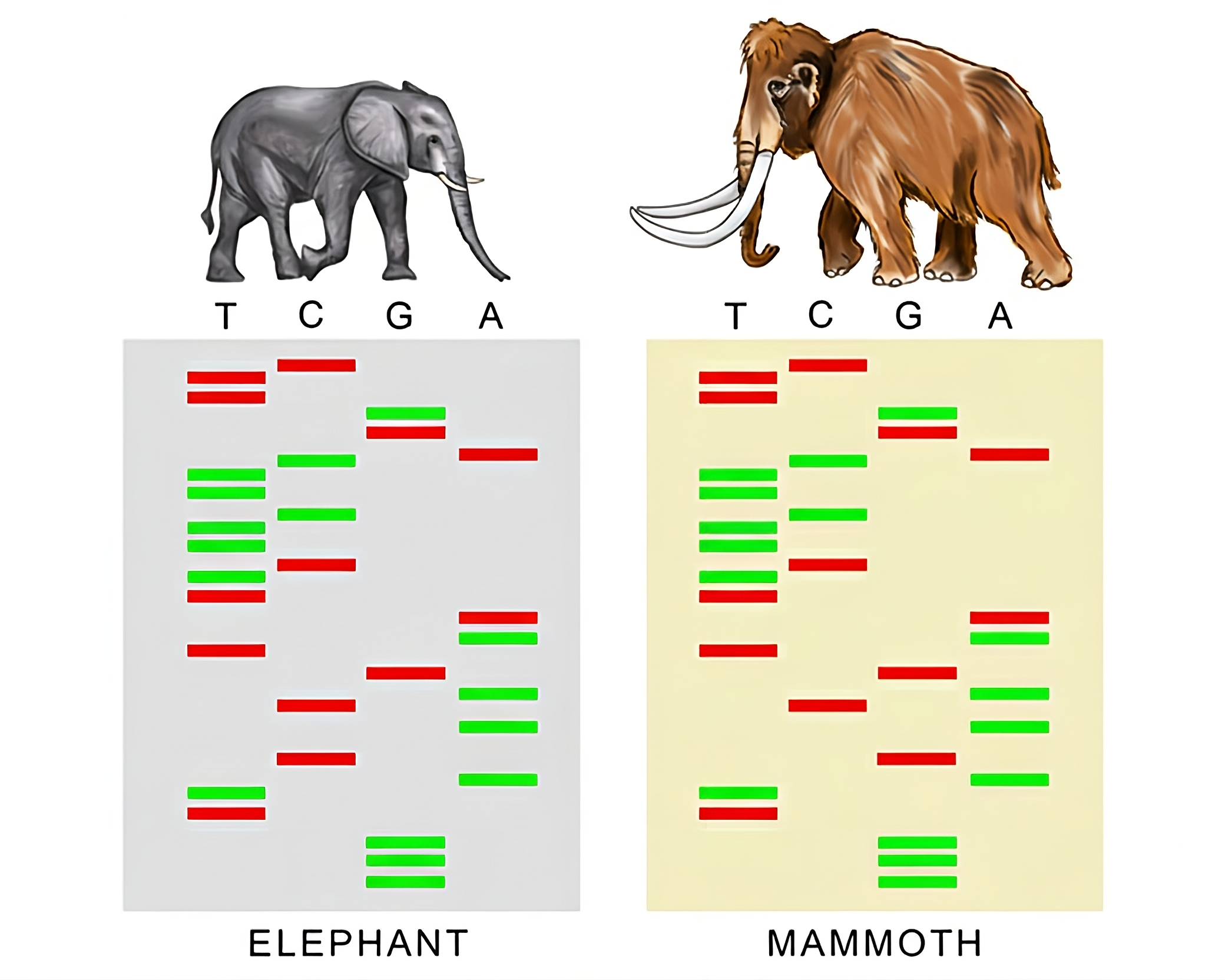

Illustration showing side-by-side DNA fragments from an Asian elephant and a woolly mammoth, used to visualize how genetic engineering identifies cold-adaptation genes for de-extinction and Arctic restoration research. © Mammoth Memory.

What Mammoth de-extinction means for climate and conservation

Beyond curiosity or nostalgia, reviving mammoths intersects ecology, climate strategy, and ethical responsibility. Experiments at Pleistocene Park in Siberia (Zimov et al.) demonstrate that large herbivores can maintain tundra grasslands, increase surface reflectivity, and slow permafrost thaw. Genetic engineering also provides insights for conservation of extant species: cold-adaptation genes inform elephant biology, disease resistance research supports endangered megafauna, and gestation technologies could aid other critically endangered animals (Bhardwaj, 2025).

Yet, these ambitions confront profound ethical and ecological questions: surrogate mothers are endangered Asian elephants, large hybrids may disrupt existing ecosystems, and even the concept of “solving climate change with mammoths” risks distraction from urgent emission reductions (Sideris, 2025; Paganeli & Galetti, 2025).

Why bring back the Mammoths?

The Mammoth steppe

In the deep freeze of prehistory, the mammoth steppe once stretched like a tawny ribbon from the Cantabrian fringe to the Beringian horizon. A world of wind-combed grasses, hooved migrations, and giants that shaped the earth with every footfall. Today, its silence feels immense — but many scientists now argue might be reversible.

Proxies, not replicas

According to Revive & Restore (n.d.), the aim is not resurrection in a literal sense, but the creation of proxies: cold-adapted hybrids shaped from the genomic memories of Mammuthus primigenius and carried in the living bodies of Asian elephants. What matters is not the perfection of their likeness but the revival of the ecological work those giants once performed.

Revive & Restore describes mammoths as “ecosystem engineers,” creatures that punched openings through shrublands, restored grasses, and pressed winter snow tight enough for the Arctic cold to penetrate downward — safeguarding the permafrost’s vast vaults of ancient carbon. Their absence has left the Arctic more vulnerable, not less.

Rewilding the frozen Earth

Dr. Sergey Zimov’s decades of fieldwork strengthens this premise: the trampling, grazing, and cycling of large herbivores can shift the fate of the ground beneath them, slowing thaw and the carbon release that shadows our future.

Genomes, too, hold lessons. Revive & Restore notes how the hemoglobin of mammoths harbors adaptations to the cold that could illuminate pathways in medicine and even guide human exploration beyond Earth. The research itself — the viral studies to protect elephants, the reproductive technologies built for proxies — may prove as valuable as any proxy creature ever born.

In this vision, biotechnologists and conservationists walk the same path: studying the past not as nostalgia, but as a set of ecological and biological tools, waiting to be reinterpreted.

Can rewilding cool the planet? Insights from Pleistocene Park

Mann (2018) widens the lens. The mammoth steppe was once the largest biome on Earth, a continent-binding sheet of grassland sustained by grazing megafauna, including the shaggy giants themselves. Its collapse was not merely the extinction of a species but the quiet unraveling of entire landscapes.

Mann describes the work underway at Harvard — synthesizing fragments of mammoth DNA, inserting them into elephant cells — and ties it to a wager, almost mythic in tone: could resurrecting part of this ancient biome cool the Arctic and shield the world from its own warming?

This vision meets the frozen earth in Pleistocene Park, where Zimov’s experiment unfolds. Mann notes that bison, musk oxen, horses, and reindeer already reshape the ground, reflecting sunlight, cooling soil, and altering carbon dynamics. Their hooves write a story of possibility — a glimpse of what mammoths might someday amplify.

Representation based on Pleistocene Park, Russia, showing bison and horses foraging in a winter landscape. The scene highlights ongoing rewilding research exploring whether large herbivores can revive grassland ecosystems and help preserve Arctic permafrost to mitigate climate warming.

To bring back the mammoth, then, is not simply to reclaim a lost wonder. It is to ask whether the memory of the planet might help heal its present wounds.

Ethical debate: reviving extinct species & ecological risk

If the dream of de-extinction glows gold at its edges, its shadows are equally deep.

Paganeli & Galetti (2025) describe how the recent creation of a “terrible wolf” proxy — in truth a re-engineered gray wolf carrying only whispers of ancient DNA — has jolted the debate. Their analysis is a warning: the ability to build a creature does not guarantee we understand the world it will enter.

Which traits? Which functions? Which values?

The past is not a simple blueprint. Which traits to recreate? Which ecological functions to prioritize? Which values do we embed in a genome? Size, behavior, metabolism — each choice alters how an organism fits (or fails to fit) into its surroundings. Even without release, there is the perennial risk of escape into ecosystems wholly unprepared for their presence.

In this view, biotechnology is not just a tool, but a force that demands humility.

Genovesi & Simberloff (2020) extend the argument. To release a proxy into the wild, they argue, is to invite the same dangers posed by non-native species: predation, competition, disease, shifts in vegetation, disruptions in hydrology and fire regimes. Ecological forecasting quickly collapses when dealing with species gone for millennia. The uncertainty is not a sidebar — it is the core of the issue.

Conservation first, experiments second

Their conclusion is sober but not hopeless: de-extinction should not be banned outright, but neither should it leap ahead of conservation. The survival of native species and the stability of modern ecosystems must outweigh hypothetical benefits of reviving the vanished.

Sideris (2025), writing for Yale Climate Connections, brings the ethical lens into sharper focus. She cautions against the narrative that mammoth proxies could solve the climate crisis. The “methane bomb,” she explains, is unlikely to detonate as often claimed, and resurrected megafauna will not stand between us and the warming we continue to accelerate.

More troubling are the ethical costs: Asian elephants — sentient, endangered, deeply social — would bear the burden of experimentation, gestation, and reproductive risk. To transform the Arctic meaningfully would require tens of thousands of hybrids, a scale bordering on the fantastical.

The danger of a beautiful distraction

In her rendering, de-extinction becomes a seductive distraction: a technological fantasy that risks weakening the urgency to protect the species we still have.

Bhardwaj (2025) frames the debate differently. For Colossal Biosciences, de-extinction is not nostalgia but strategy. He lays out the economic stakes: half of the world’s GDP depends on nature, and ecological collapse threatens trillions in value by 2030.

In this telling, biotechnology is a lifeline. Colossal’s work with mammoth genomes, Tasmanian tigers, and dodos has already attracted extraordinary investment, turning the company into Texas’s first “decacorn.” The mammoth, in this narrative, is part of a broader effort to restore lost ecological functions, reduce permafrost emissions, and accelerate conservation tech — from artificial wombs to vaccines for elephants and predator-resistance in quolls.

To Bhardwaj, de-extinction is not a fantasy but a frontier: high-risk, high-reward, and undeniably intertwined with the economic and ecological fabric of the coming century.

Benefits vs. risks

The promise of de-extinction sits at a crossroads between wonder and warning.

Potential benefits:

Reviving lost ecological functions (Revive & Restore; Mann; Zimov)

Mitigating permafrost thaw and carbon release (Mann; Bhardwaj)

Advancing medicine and biotechnology (Revive & Restore; Bhardwaj)

Accelerating conservation for living species (Bhardwaj; Revive & Restore)

Major risks:

Ecological destabilization and invasiveness (Genovesi & Simberloff; Paganeli & Galetti)

Ethical harm to surrogate species (Sideris)

Technological “distraction” from real climate action (Sideris)

False sense of security that undermines conservation (Paganeli & Galetti; Genovesi & Simberloff)

Between these poles lies a question not only of science, but of philosophy:

Should humanity rebuild what it destroyed, or should it learn to protect what remains?

What Mammoth revival reveals about humanity

What does it say about us that we dream of returning giants to a world still trembling from our touch?

Perhaps this desire carries a longing — not simply for the creatures themselves, but for the version of Earth they once embodied. But nostalgia is not enough.

Is longing a valid engine for conservation?

Or does it risk blinding us to the ecosystems that still pulse with life and need — now, urgently, desperately?

A mammoth, even if reborn, cannot mend our relationship with the living world.

But perhaps the idea of one can remind us that extinction is not theoretical — it is a wound we leave behind.

The real work also begins elsewhere:

Protecting habitats that still breathe.

Supporting conservation projects that save species on the brink.

Rewilding landscapes where native life can return.

Reducing the emissions that heat the skies and acidify the seas.

Donating, planting trees, restoring forests, backing the communities who defend the Earth daily.

A close-up image of a family of elephants gathered in soft evening light. They reflect the moral and ecological questions at the heart of mammoth revival, what humanity owes to the species still alive today, and how de-extinction intersects with conservation, responsibility, and coexistence.

And maybe, in doing so, we honor both the world that was, and the world that could still be saved.

When we imagine the return of the woolly mammoth, we are not merely chasing shadows of the past, we are holding up a mirror to ourselves. What does it say about humanity that we long to resurrect the very creatures we once helped drive to extinction? That we dream of repairing the tundra with giants long gone, while forests burn and species vanish around us?

Nostalgia, powerful though it may be, is not conservation. It is a lens through which we hope to glimpse a world we have lost, a world we might still save if we turn our attention to the ecosystems that remain. The mammoth cannot undo the mistakes of the past; it can only serve as a symbol, a catalyst for reflection, and perhaps a partner in restoring balance where we still can. The future of our planet will not be shaped by reviving the past alone, but by the choices we make today.

If we cannot yet undo extinction, perhaps we can at least honor life by ensuring that what remains never disappears. Can we rise to the responsibility, or will the echoes of lost giants be all that future generations inherit?

References

Barney, O. (2025). Mammoths and Mastodons Made a Great Ice Age Team. Natural History Museum of Utah. https://nhmu.utah.edu/articles/mammoths-and-mastodons-made-great-ice-age-team

Bhardwaj, D. (2025). How the Woolly Mammoth could prevent trillions in economic loss. Inc. https://www.inc.com/divya-bhardwaj/how-the-woolly-mammoth-could-prevent-trillions-in-economic-loss/91108925

Colossal Biosciences. (n.d.). The Mammoth. https://colossal.com/mammoth/

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2025). Woolly mammoth. https://www.britannica.com/animal/woolly-mammoth

Genovesi, P., & Simberloff, D. (2020). “De-extinction” in conservation: Assessing risks of releasing “resurrected” species. Journal for Nature Conservation, Volume 56, 2020, 125838, ISSN 1617-1381, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnc.2020.125838.

Gross, L. (2006). Reading the Evolutionary History of the Woolly Mammoth in Its Mitochondrial Genome. PLoS Biol. 2006 Mar;4(3):e74. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040074. Epub 2006 Feb 7. PMID: 20076539; PMCID: PMC1360100.

Ianello, M., Sevciuc, F., Dvila Assumpo, M. E. O., & Antnio, J. (2013). Genetic Engineering and Cloning: Focus on Animal Biotechnology. InTech. DOI: 10.5772/56071

Kuta, S. (2019). What Killed the Last Woolly Mammoths? Scientists Say It Wasn’t Inbreeding. Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/what-killed-the-last-woolly-mammoths-scientists-say-it-wasnt-inbreeding-180984632/

Mann, P. (2018). Can Bringing Back Mammoths Help Stop Climate Change? Smithsonian Magazine. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/can-bringing-back-mammoths-stop-climate-change-180969072/

Murchie, T. J. (n.d.). Ancient DNA suggests woolly mammoths roamed Earth more recently than previously thought. Arctic Focus. https://www.arcticfocus.org/stories/ancient-dna-suggests-woolly-mammoths-roamed-earth-more-recently-previously-thought/?gad_source=1&gad_campaignid=22419404330&gbraid=0AAAAA93WQMLdHAzVvunX6Dtx-Fbk4iZtv&gclid=CjwKCAiAlrXJBhBAEiwA-5pgwh2Gv373brtw1UUAnCXouaVfMdMSoAUCj9spIAnyP3mYRdk4pUo7rhoCr3sQAvD_BwE

National Park Service. (2015). Woolly Mammoth: Page 2. U.S. Department of the Interior. https://www.nps.gov/bela/learn/historyculture/woolly-mammoth-page-2.htm

Paganeli, B., & Galetti, M. (2025). De-Extinction at a Crossroads: Ecology, Ethics, and the Future of Conservation in the Biotech Age. Ecol Lett. 2025 Sep;28(9):e70217. DOI: 10.1111/ele.70217. PMID: 40982394; PMCID: PMC12453136.

Revive & Restore. (n.d.). Woolly Mammoth: About the species. https://reviverestore.org/projects/woolly-mammoth/about-the-species/

Revive & Restore. (n.d.). Woolly Mammoth revival: why bring back the mammoth? https://reviverestore.org/projects/woolly-mammoth/why-bring-it-back/

Stephens, T. (2021, May). Oldest DNA sequences reveal how mammoths evolved. Genomics Institute. University of California, Santa Cruz. https://genomics.ucsc.edu/news/2021/05/oldest-dna-sequences-reveal-how-mammoths-evolved/

Sideris, L. H. (2025, April). Bringing back the mammoth won’t fix the future. Yale Climate Connections. https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2025/04/bringing-back-the-mammoth-wont-fix-the-future/

Science. (2005). Scientists Resurrect Woolly Mammoth DNA. https://www.science.org/content/article/scientists-resurrect-woolly-mammoth-dna

Science Learning Hub. (2023). Extracting ancient DNA. https://www.sciencelearn.org.nz/resources/2024-extracting-ancient-dna