Lost in the canopy: explorers who vanished into the world’s densest forests

A vintage compass and magnifying glass placed on an antique world map, representing the navigation systems used by early explorers before entering dense forests where orientation collapses. The image reflects how traditional tools—maps, compasses, and fixed references—become unreliable under heavy canopy, contributing to repeated patterns of disappearance in rainforest environments such as the Amazon, Congo Basin, and Southeast Asian jungles.

Disappearance as a pattern, not an accident

When people vanish in forests, the language of error is applied: a wrong turn, a failed map, poor judgment. This framing is misleading.

Across centuries and continents, the same sequence repeats. Dense forests do not produce sudden disasters. They dismantle the conditions required for return.

Orientation fails first. Canopy eliminates horizon. Rivers misdirect rather than guide. Trails degrade faster than memory. Movement continues, but reference disappears.

Next, continuity breaks. Supplies depend on timing, dryness, and intact materials — none of which forests allow. Paper dissolves. Metal corrodes. Food spoils. Small delays compound until logistics collapse.

Then communication ends. Once contact is lost, an expedition exits shared time. Concern arrives only after recoverability has already passed.

This is not bad luck. It is environment acting at scale.

Forests do not preserve evidence or expose it. They convert it. Human presence is absorbed into biological process. Camps decay before they can be found. Bodies do not remain stable long enough to testify.

Disappearance here is not an event but a condition. One can survive while becoming unreachable. Continue moving while already lost.

Some environments defeat the body.

Forests defeat systems.

Why dense forests defeat human systems

A dense tropical forest with overlapping vegetation, tall tree trunks, and a closed canopy that blocks long-distance sightlines. The image illustrates how rainforest environments eliminate horizons, distort orientation, and erase visual reference points, rendering human navigation systems unreliable. Such conditions explain why dense forests consistently defeat exploration, communication, and recovery systems, leading to repeated patterns of disappearance.

Human systems are built on three pillars: Sight, Steel, and Certainty. In a dense forest, all three are not just challenged—they are rendered hallucinations. A forest is not a "setting" for a disaster; it is a digestive system for human logic.

Civilization is a product of the long view. Humans navigate by looking at things far away (stars, mountains, towers) to understand where they are now. The forest kills the "far away." When the world is limited to a six-foot radius of green wall, the brain begins to glitch. Without a horizon, the inner ear and the ocular nerve stop communicating. Humans don't just get lost; they lose the concept of a straight line. In the deep woods, "forward" is a guess, and a guess is a death sentence.

The great solvent

People think of the forest as solid wood and stone. It isn't. It’s a high-speed chemical reaction.

The Humidity: It is a slow-motion flood. It doesn't just make the person sweat; it turns its boots into sponges, maps into mush, and skin into a gateway for fungi.

The Decay: In the jungle, the "ground" is a lie. Explorers are walking on a layer of rotting ghosts—thousands of years of fallen trees and dead things that haven't quite finished liquefying.

The Edit: Humans leave marks to survive. They blaze trees, they stack stones, they pack down dirt. The forest "edits" these marks in real-time. Vines move inches in a day; rain fills footprints in minutes. The forest has an undo button.

The shape of loss

Why do we find bodies in the desert but only "mysteries" in the forest?

Deserts Preserve: The sun mummifies.

Oceans Return: The tide eventually gives up its secrets.

Forests Assimilate: Within forty-eight hours of a human system failing, the forest begins to reclaim the components. Acidic soil dissolves bone. Insects disassemble cloth. The forest doesn't leave a "site"—it grows through it.

The psychological spiral

Studies in stress and survival psychology show that losing orientation in extreme environments activates an intense stress response, with increases in cortisol that impair working memory and judgment under pressure (Arnsten, 2009; Sapolsky, 2015). Anxiety and hyper-focused attention on perceived threats reduce planning capacity and promote impulsive decision-making (Morgan et al., 2006). In addition, the combination of prolonged uncertainty and social isolation is associated with greater cognitive confusion, mood disturbances, and mental fatigue (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009). Taken together, the evidence indicates that being lost produces a measurable psychological contraction, marked by stress, cognitive impairment, and sustained emotional load.

The myth of “blank” wilderness

Explorers didn’t just get lost in forests — they erased them on paper.

Nineteenth- and early twentieth-century maps render dense forests as pale emptiness: unknown, unexplored, unclaimed. These blanks were not gaps in knowledge. They were choices, a declaration that the land was free to enter, measure, and control.

In reality, forests were alive — inhabited, navigated, and understood by Indigenous peoples. Paths shifted, landmarks were relational, knowledge flowed through practice, not print. European explorers, trained to measure and fix, read this fluidity as absence.

The result: a conceptual trap. Blank maps created blank expectations. Disappearance was framed as mystery, not inevitability. Indigenous knowledge was ignored. Forests were not misunderstood — they were systematically misimagined.

The type of person who enters — and does not return

Explorers advancing into thick forest undergrowth, emphasizing momentum, conviction, and the tendency to prioritize continuation over reassessment.

Disappearance is selective. Not everyone vanishes. Those who do are driven by obsession, conviction, and detachment.

They enter believing the forest holds what the world cannot: lost truths, hidden worlds, freedom. Risk is irrelevant; stopping is unthinkable. Communication fades, obligations slip, ties dissolve. Disorientation is an event. Evasion is a habit.

Forests accelerate it. Trails vanish. Landmarks disappear. Forward motion becomes irresistible, survival secondary. Intent is the first variable to dissolve; presence is the second.

This is not tragedy; it is design. A dense forest does not erase by chance. It facilitates disappearance with total efficiency.

Case studies: when the pattern becomes predictable

A. Percy Fawcett — The Amazon as conceptual terrain

Percy Fawcett’s final expedition, launched in 1925, departed from the town of Cuiabá, in central Brazil, with the aim of penetrating the upper reaches of the Rio Xingu and the unexplored borderlands between Bolivia and Brazil. His declared goal was to locate the legendary city he called Z, which he conceived as evidence of a highly organized civilization that predated European influence in South America. Z was less a mapped destination than a conceptual corrective — a challenge to prevailing assumptions about progress, primitivism, and the limits of human organization.

The expedition included his eldest son, Jack, and a small party of trusted companions. Fawcett’s planning emphasized mobility over security: travel was light, supplies minimal, and communication with the outside deliberately constrained. He relied on indigenous guides when possible, though their knowledge was filtered through his expectations of what the forest should yield. Routes were determined by rivers, seasonal trails, and prior reconnaissance, yet all were provisional, shifting with rainfall and growth.

During the journey, the forest imposed constant challenges. Navigation collapsed under dense canopy and river systems that twisted unpredictably. High humidity accelerated material decay: tents, food, and equipment deteriorated within weeks. Insects, disease, and fungal growth threatened both health and provisions. The forest did not act intentionally, yet these conditions systematically dismantled the expedition’s logistical framework.

As Fawcett pressed onward, he limited backtracking and relied increasingly on intuition and prior observation, a pattern consistent with his psychological profile: forward momentum as coherence, retreat as narrative failure. Disappearance was not sudden but the eventual outcome of the forest’s structural effects — misread terrain, severed supply chains, environmental pressure, and the compounded isolation of human systems from corrective oversight.

When Fawcett vanished, the absence of bodies, camp remains, or definitive route allowed Z to persist as an idea rather than a resolved failure. What survived were conflicting reports, altered maps, and speculation layered atop absence. The forest did not conceal a body. It dissolved the entire evidentiary chain.

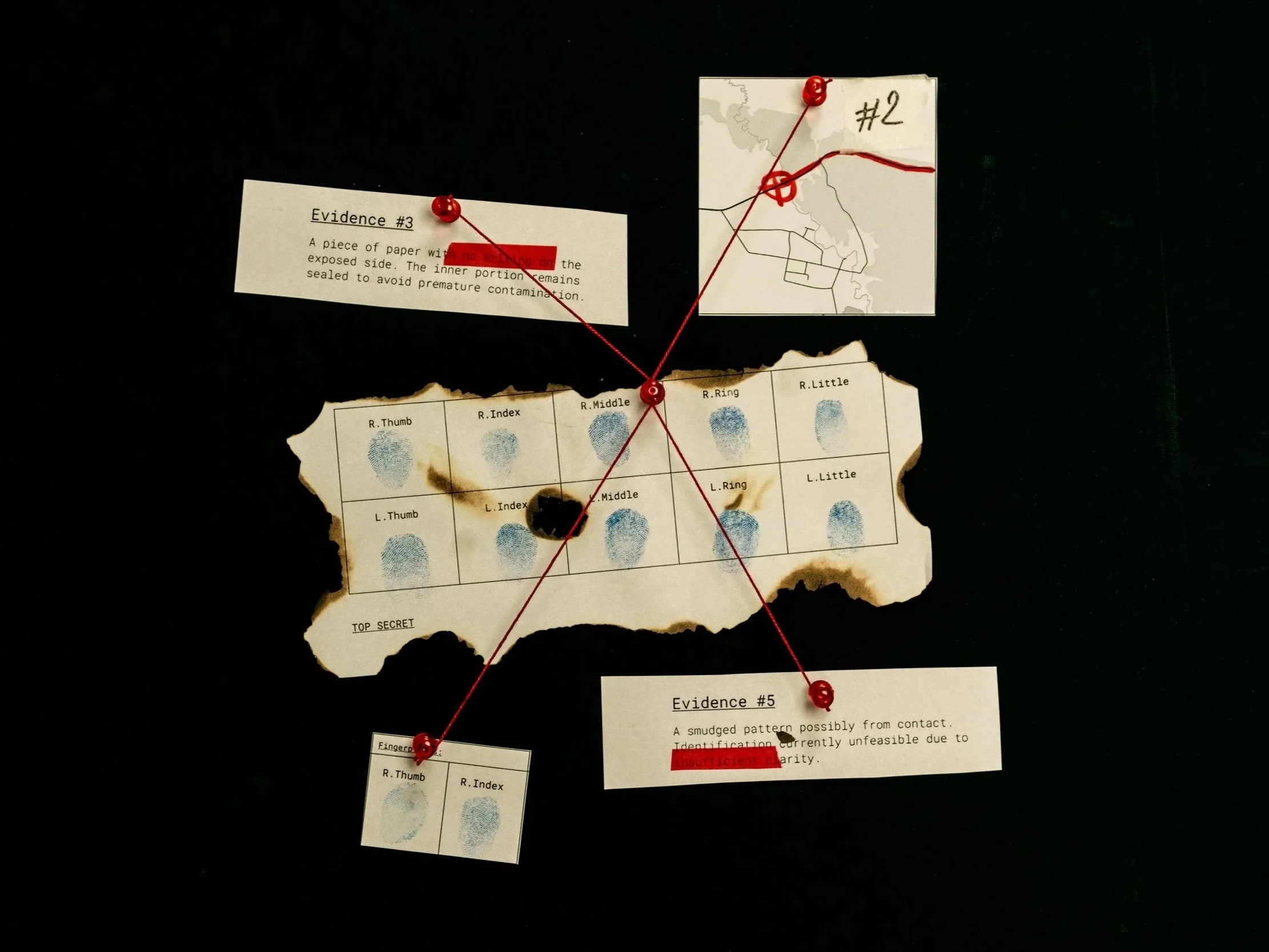

A dark forensic-style display shows scorched fingerprint sheets, pinned evidence notes, and a fragmented map connected by red string. The materials appear damaged and incomplete, suggesting decay, lost continuity, and failed reconstruction. The image visually represents the disappearance of British explorer Percy Fawcett in the Amazon, where environmental conditions erased physical evidence and prevented recovery. It reflects how dense forests dismantle human systems of proof, leaving absence rather than answers.

B. The searchers: lost in plain sight

What followed Fawcett’s disappearance reveals the recursive nature of forest loss. Numerous expeditions entered the Amazon not to explore terrain, but to resolve absence. Their objective was not a place but a person.

These searchers inherited the same structural vulnerabilities as the original expedition, often amplified by urgency. They relied on fragmented reports, contradictory Indigenous accounts, and speculative mapping. Each attempt to follow Fawcett’s trail recreated the conditions that had erased it. The forest did not differentiate between original intent and secondary pursuit.

Some of these searchers vanished as well. Others emerged with stories that could not be verified — sightings, rumors, partial artifacts without context. The absence they sought to close multiplied instead. Disappearance became layered, each loss compounding the previous one.

This recursion exposes a critical feature of forest disappearance: once an expedition vanishes, the conditions that produced its loss are rarely re-evaluated. The forest is re-entered under the same assumptions, and the pattern repeats.

C. Parallel vanishings across forest systems

The Amazon is not anomalous.. The same structure appears in other dense forest environments, regardless of continent or culture.

A similar structure appears in the Congo Basin. Late-19th-century expeditions pursuing river sources, trade corridors, or ethnographic documentation encountered an environment that dismantled navigation with mechanical efficiency. Dense understory blocked line-of-sight movement; rivers shifted course between seasons; camps were swallowed by vegetation within weeks. During the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition (1887–1889), led by Henry Morton Stanley, hundreds died not in battle but through fragmentation, starvation, disease, and disorientation. Smaller advance parties disappeared completely. Search efforts failed because nothing stable remained to search from. Camps left behind did not persist as landmarks. The forest re-absorbed them before return was possible.

An explorer scanning a dense rainforest canopy with binoculars, illustrating how dense forest environments across the Amazon, Congo, and Southeast Asia consistently dismantle navigation, visibility, and human survival systems.

In the Darién Gap, straddling Panama and Colombia, disappearance followed a slightly different but equally final logic. Surveyors, prospectors, and would-be canal planners in the 19th and early 20th centuries consistently underestimated the ground itself. What appears as solid land on maps is often swamp, floodplain, or unstable clay. Rivers—assumed to function as natural guides—double back, split, or dead-end into impassable mangrove. Expeditions attempting crossings frequently fragmented when forward movement became impossible. Once separated, groups could not retrace their paths. Rescue attempts were speculative, based on last assumptions rather than coordinates. Many vanished without any wreckage, camps, or remains ever being located.

The pattern repeats again in Southeast Asian rainforests, particularly in colonial-era expeditions into the interiors of Laos, Cambodia, Borneo, and New Guinea. French and Dutch exploration teams attempting to map watersheds or assert territorial control reported entire detachments failing to return. Journals ended mid-entry. Supply caches were never reached. Later searches found nothing but forest that no longer bore signs of passage. In Borneo, multiple early 20th-century interior mapping missions simply ceased communication, leaving behind revised maps marked with uncertainty. The terrain produced silence, not evidence.

A similar erasure occurred decades later in the Lacandon Jungle of southern Mexico. Mid-twentieth-century anthropological and surveying expeditions entering dense rainforest regions of Chiapas reported the disappearance of individual team members during early incursions. Some were presumed dead; none were recovered.

Across all of these regions, the outcome is strikingly consistent: loss without remains, silence without coordinates. The forest retains no archive.

The motives differ — exploration, extraction, mapping, proof, rescue — but the structure does not. Once systems designed for visibility, continuity, and return enter environments organized around concealment, decay, and constant change, correction becomes difficult. Withdrawal is postponed. Momentum replaces judgment.

What the cases share

What unites these disappearances is not recklessness, incompetence, or heroism. It is convergence.

Each case aligns the same conditions:

A misimagined environment, framed as blank, navigable, or ultimately legible

A psychological orientation toward continuation, where turning back is treated as failure rather than data

Logistical systems unsuited to humidity and decay, where equipment rots, markers vanish, and time destroys reference points

An ecosystem that removes trace, rather than preserving it through wreckage or remains

Once these conditions converge, disappearance stops being exceptional. It becomes statistically likely.

The forest does not need to act decisively. It does not ambush, pursue, or trap. It only persists. Vegetation grows. Water moves. Ground shifts. Markers decay. Orientation collapses gradually, then completely.

By the time individuals vanish from record, they have usually crossed a threshold long before — a point at which retrieval is no longer a realistic outcome but a theoretical hope.

Why forests keep secrets better than deserts or oceans

Disappearances do not occur equally across landscapes. Deserts tend to preserve evidence: arid conditions slow decay, footprints last, and objects remain exposed. The ocean destroys violently but often returns material—wreckage, cargo, signals, coordinates—allowing events to be reconstructed even when bodies are lost.

Forests function differently. Warmth, moisture, fungi, insects, and bacteria rapidly break down organic material, while vegetation closes trails and erases human markers within days or weeks. Visibility is limited, navigation is unreliable, and terrain changes seasonally. As a result, bodies, equipment, and camps are not hidden or displaced—they are biologically dismantled and absorbed.

In forest environments, disappearance is not a mystery of concealment but a predictable ecological process.

After the disappearance

Forest disappearances rarely resolve. Without remains, death cannot be formally confirmed, leaving families in prolonged uncertainty and legal systems unable to close cases. The grief remains an open circuit, denied the finality of a record or the peace of a conclusion.

Records degrade over time. Maps are revised, then abandoned; routes are removed rather than corrected. Official reports end without findings, leaving behind fragments—last letters, last coordinates, incomplete assumptions—with no verified outcomes.

In this evidentiary vacuum, myth replaces analysis. Individuals are recast as symbols of obsession or heroism, while environmental and logistical factors fade into the background. This shift does not clarify events; it prevents learning by obscuring the systemic conditions that made disappearance likely.

The refusal of closure

Forests do not offer endings.

They do not resolve disappearance, confirm death, or return answers on human timelines.

Disappearance in forests is not a puzzle waiting to be solved. It is a state that remains once retrieval becomes structurally impossible. Nature does not correct this. It does not reveal or explain. It simply continues.

This is why these stories endure. Not because they promise discovery, but because they deny it.

The forest is one of the few environments where uncertainty survives intact.

And so we keep telling these stories — not to uncover what was lost, but to circle what cannot be recovered. To remind ourselves that some places are not designed to answer us.

They are constants, not variables.

References

Arnsten, A. F. T. (2009). Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 410–422.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(10), 447–454.

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2026). Why is crossing the Darién Gap so dangerous? https://www.britannica.com/question/Why-is-crossing-the-Darien-Gap-so-dangerous

Francis Garnier & Ernest Doudart de Lagrée. Exploratory Expedition Through Indochina (Mekong Expedition 1866–1868).

Grann, David. The Lost City of Z: A Tale of Deadly Obsession in the Amazon.

Doubleday, 2009.Jeal, Tim. Stanley: The Impossible Life of Africa’s Greatest Explorer. Yale University Press, 2007.

King, Victor T., ed. Explorers of South-East Asia: Six Lives. Oxford University Press, 1995.

Morgan, C. A., Doran, A., Steffian, G., Hazlett, G., & Southwick, S. M. (2006). Stress-induced deficits in working memory and visuo-constructive abilities in special operations soldiers. Biological Psychiatry, 60(7), 722–729.

Sapolsky, R. M. (2015). Stress and the brain: Individual variability and the inverted-U. Nature Neuroscience, 18(10), 1344–1346.

Stanley, Henry Morton. In Darkest Africa. 1890.